Pope Francis recently shone a spotlight on South Sudan in East Africa, when he visited the fledgling country to plea for peace.

Established in 2011, South Sudan is the youngest country in the world and has seen civil unrest and bloody conflict for years. Pope Francis' visit was hugely symbolic, as he showed the Church's wish to see the country and its people grow and prosper as they continue to build their nation.

But as is normally the case with these papal visits, they are carefully choreographed and specifically stage-managed to show the very best a country has to offer. The world’s TV cameras captured the smiling handshakes between the Pope and the president, the country’s Church leaders warmly welcoming their Holy Father, and the thousands of well-wishers who turned up for the papal Mass in the capital, all waving South Sudanese and Vatican flags.

Again, don’t get me wrong, these trips hold immense value and have become an integral part of any papacy, but what they often fail to do is show the true reality of life for so many in the country.

Because in a country like South Sudan, it’s away from the smiling faces waving miniature flags, and the opportunist politicians having their pictures taken, that millions of the nation’s citizens lay weak and hungry, some even slowly starving to death.

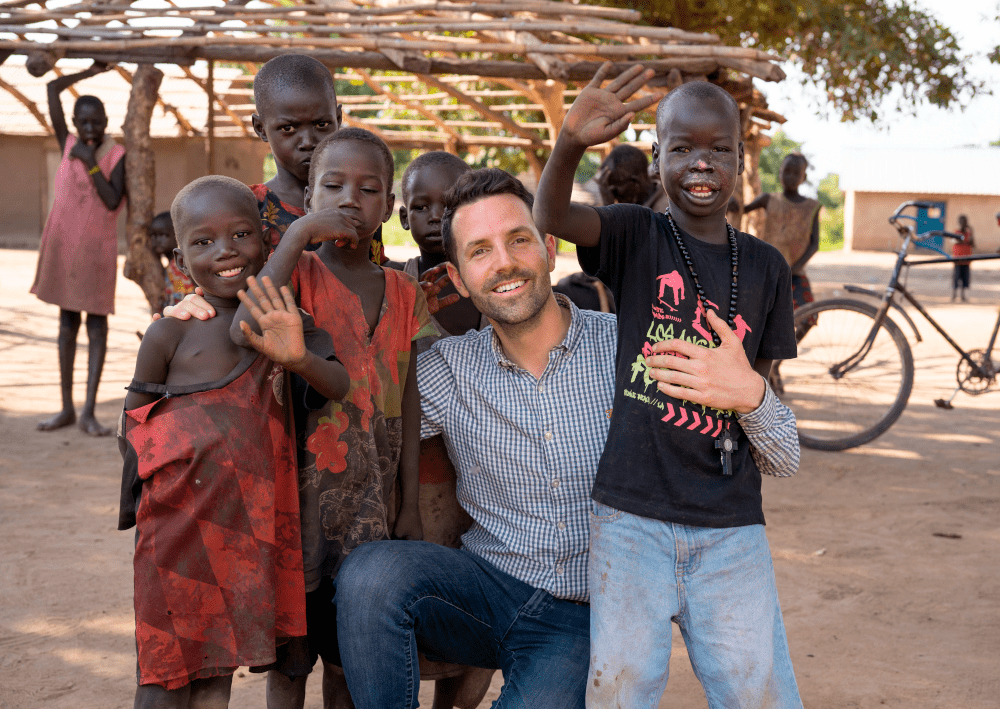

Last year, a few weeks ahead of the Pope’s originally planned trip, I traveled to South Sudan for EWTN News In Depth to get a real sense of how people in some of the hardest-hit regions live, and what I witnessed was hard to believe — especially in the central rural region of Rumbek, where I visited a leprosy colony, but I’ll get to that in a moment.

When we landed in Juba, the capital, the first thing my cameraman, Patrick Leonard, and I realized was that we were in a dangerous country. No sooner had we stepped off the plane, an airport official approached us, pulled us to one side, and asked for a bribe to “help us through the airport.” This would happen again at passport control, as there was “something wrong with our documents,” and again at the baggage carousel, to “retrieve our luggage,” and at security when leaving the airport, to “allow our equipment to leave.” I quickly realized this was part of the reality of daily life in South Sudan. When we met our local contact, Irish lay missionary Noeleen Loughran, she was waiting for us with four policemen in military uniforms holding machine guns. They would be with us for the entire trip, to offer us protection — again, at a cost. But I was told by Noeleen that here in South Sudan it was vital we had these armed guards with us at all times.

The first place we visited was right in the middle of Juba. It is estimated that there are around 3,000 “street kids” in the city. As the name suggests, these are homeless children who roam the streets fending for themselves. Many of their parents were killed in the civil war; and now, as orphans, they do whatever they can to try and survive. As you can imagine, the streets are a dangerous place, with violence, drugs and killings commonplace. We went to an area notorious for having many street children, and as soon as we went out to film, they all ran over — pleading for money. Of course, they see white people as being rich beyond their wildest dreams; and in comparison, they are absolutely right. I was told not to give them any money, as it would cause mayhem. But after a few minutes, I found myself putting my hand in my pocket and taking out a few single dollars to hand out. The kids started to violently push each other out of the way and shout as they snatched the money out of my hands. The others who didn’t get any ran over, pleading for some. It was then I noticed in their eyes and smelt from their breath that some of them, as young as 11 or 12, were intoxicated. The only thing giving them comfort in their life is a quick fix from alcohol or drugs. As we pulled away in our jeep, I saw two boys start to fist-fight and fall in the dirt.

It was heartbreaking.

We drove to an orphanage outside the capital called St. Clare’s House, where some of the street kids are brought by local priests and nuns. The orphanage is doing the best it can, but the conditions inside were still pretty bleak. Inside walls were covered in dirt, the children all slept in crowded rooms, and flies swarmed around their food ... but still, it's better than the streets, one of the older boys told me. “Momma Betty,” as she’s known, is the woman in charge, and she showed me around. She brought me into a small room where a sick baby, lying on a bed, was covered in sweat. There is no national power grid in South Sudan, and so they have a small solar panel on the roof connected to large car batteries. But the system is broken and in need of repair. So when it gets tremendously hot, the only solution, really, is finding shade. But that does little to escape the scorching African sun. When I asked Betty why the government doesn’t fund the house, she says that when they ask the government for money, they just say they don’t have any — it’s that simple. Of course, we know it’s not. South Sudan is regarded as one of the most corrupt countries in the world, where even foreign aid and financial support sent to help people like these often goes “missing.”

The nuns working in this small orphanage are like angels. They smile beautifully at the children as they hold them. I’m told that many of the children have been traumatized from living on the streets and need so much help from the nuns to overcome the psychological damage they’ve developed. One tall nun tells me that she makes sure, despite the fact that they are poor, orphaned street kids, that they know they are “loved, valued and unique” — something they have never before heard in their lives.

The conditions these street children have to face was hard to comprehend, but nothing prepared me for the most shocking place I visited while in South Sudan: a leprosy colony. Hidden away in a remote area in the center of the country is a community where hundreds, maybe even thousands, of people live with the infectious disease. I, perhaps like you, presumed that leprosy was a thing of the past and only ever heard about in biblical terms: Jesus cleaning and curing the leper. So you can imagine my disbelief when I stepped out of our jeep and, in the sharp African sun, looked around at the small wooden huts and the people standing around them. Excited to see visitors, they came out dressed in the best of the very little clothes they had. They welcomed us with singing and clapping and were not intimidated at all by the armed police walking behind us. For them, this is South Sudan. This is normal.

Walking towards them I was drawn to their radiant smiles and outstretched arms. It was when I looked down at their clapping hands that I noticed many of them were missing fingers, some missing entire hands. Some had crutches because where their feet once were, there are only large stumps. I later learned that their limbs had been amputated — by themselves — to prevent the further spread of leprosy. A person in the community would act as the “doctor” and perform the task of removing infected fingers, toes and other limbs. For the “lucky” ones, it would stop the spread of the disease to other parts of their body. But for others it can be too late, if the leprosy has already spread too much.

I spoke to Noeleen about this, the Irish lay missionary who works to bring relief to the people here, and what she told me was truly horrific. She explained that, in the past, when some of the people became so weak and feeble, they would be dragged away during the night by the wild hyenas. Again, it’s hard to believe that people suffer this terrible fate in this day and age.

We spent a few days in the leprosy colony, talking with the people and filming as much of their lives as we could. I felt the responsibility of bringing their story to our EWTN viewers all over the world and so wanted to make sure we got as much information and footage as possible. It was hard for us to capture the enormity of their suffering and pain on camera, and it’s even harder for me to try and articulate it here in this article.

But try to imagine a life where you have no electricity in your home, no running water to clean yourself, torrential rain flood your mud hut, and then there are periods of scorching leaving the land barren. Every day, you must think of where your food will come from — for you and your children. You watch your children and the ones you love the most becoming weaker and weaker, picking up more diseases due to malnourishment and lack of hygiene. You hope and pray they won’t be infected with the leprosy that you have. On top of this, you have to worry about wild animals. You have to try and survive — and all of this because you are living in dire poverty. You live in this leprosy colony not by choice, but because you are outcasts, banished from other towns and villages, as you are regarded as unclean and unsafe. You are isolated and alone.

One little boy I met, Tarcoth, lives in the colony with his mother, who is quiet and just stares ahead when you talk to her. Noeleen tells me she endured psychological trauma after her son developed leprosy on his face. It was just too much for her to handle, and she shut down. Noeleen often takes care of him in her own home close by, but she will not be able to do this forever. He is such a beautiful boy who is full of life and positivity, despite the pain and suffering he feels. He followed me and my cameraman, Patrick, around as we filmed and was fascinated by our equipment. He watched in wonder as we flew a drone through the air to get some aerial shots of the community. Around his beautiful smile, his face is disfigured and covered in painful sores and scabs. The terrible bacterial disease is doing its worst. Thankfully, he is now receiving medication for his condition, but with it having already done so much damage, the future for him is hard to predict.

It seems the government in South Sudan does not have the means, or most likely, the interest, in caring for these people. To put it bluntly, they are left out of the way to die. Life is cheap, in their view: Keep them out of sight and out of mind. So it is left to others, like the Catholic Church and lay Catholic missionaries such as Noeleen Loughran, to try and help the people in any way they can. But the reality is that they need money to do this. Thankfully, an organization in the U.S. called the Sudan Relief Fund heard the plight of these people and responded, sending large sums of money to the region to get the people medication, food and in some cases build them more secure and sheltered huts. As most of their homes are just small huts made from sticks and wood, it was easy for wild animals like hyenas to attack. And in the rainy season, the flood waters would carry disease into the homes. Some have better living conditions. But most do not.

I left South Sudan with a heavy heart, because even though volunteers like Noeleen and the incredible work of the Sudan Relief Fund provide some hope, there are millions of people who are suffering so terribly, and their condition doesn’t seem to be getting any better. And now, after South Sudan faced a massive crop failure due to drought, the World Food Programme predicts over a million of its people could soon die of starvation.

So following the visit of Pope Francis, and while the images of him driving through the capital are still fresh in our memory, it’s important that we raise awareness of the forgotten souls of South Sudan and the horrific reality they have to face every single day.

To donate and learn more about the Sudan Relief Fund please visit here.

Originally from Ireland, Colm Flynn is a reporter for EWTN News based in Rome. He brings viewers all over the world as he reports on incredible human interest stories of how faith inspires people in their lives. At the Vatican he covers major papal events as well as other news from the Catholic Church.